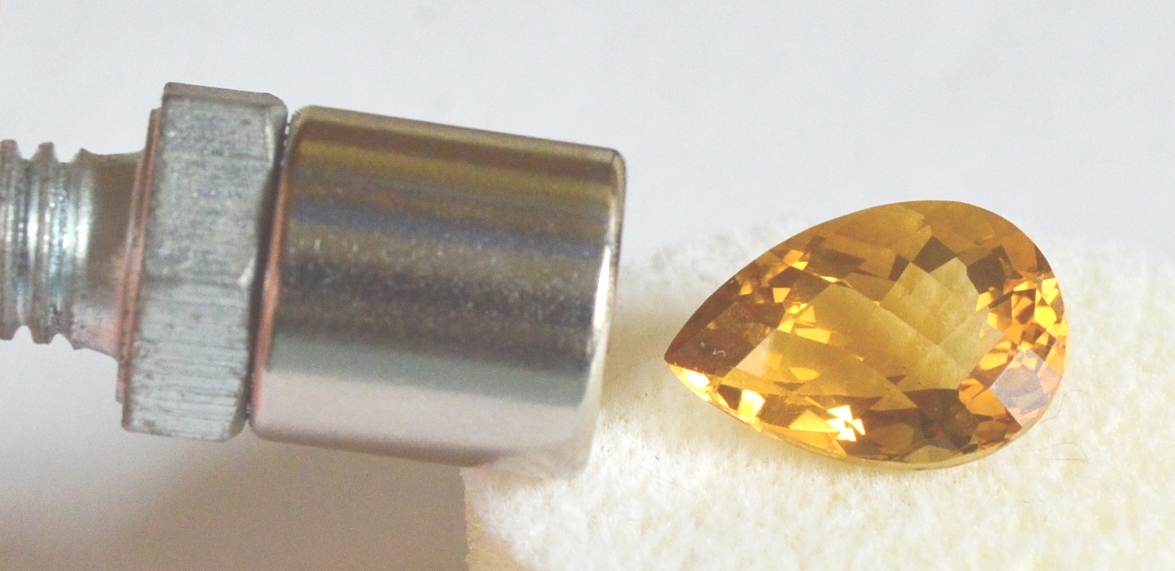

Diamagnetic Response (blue Topaz)

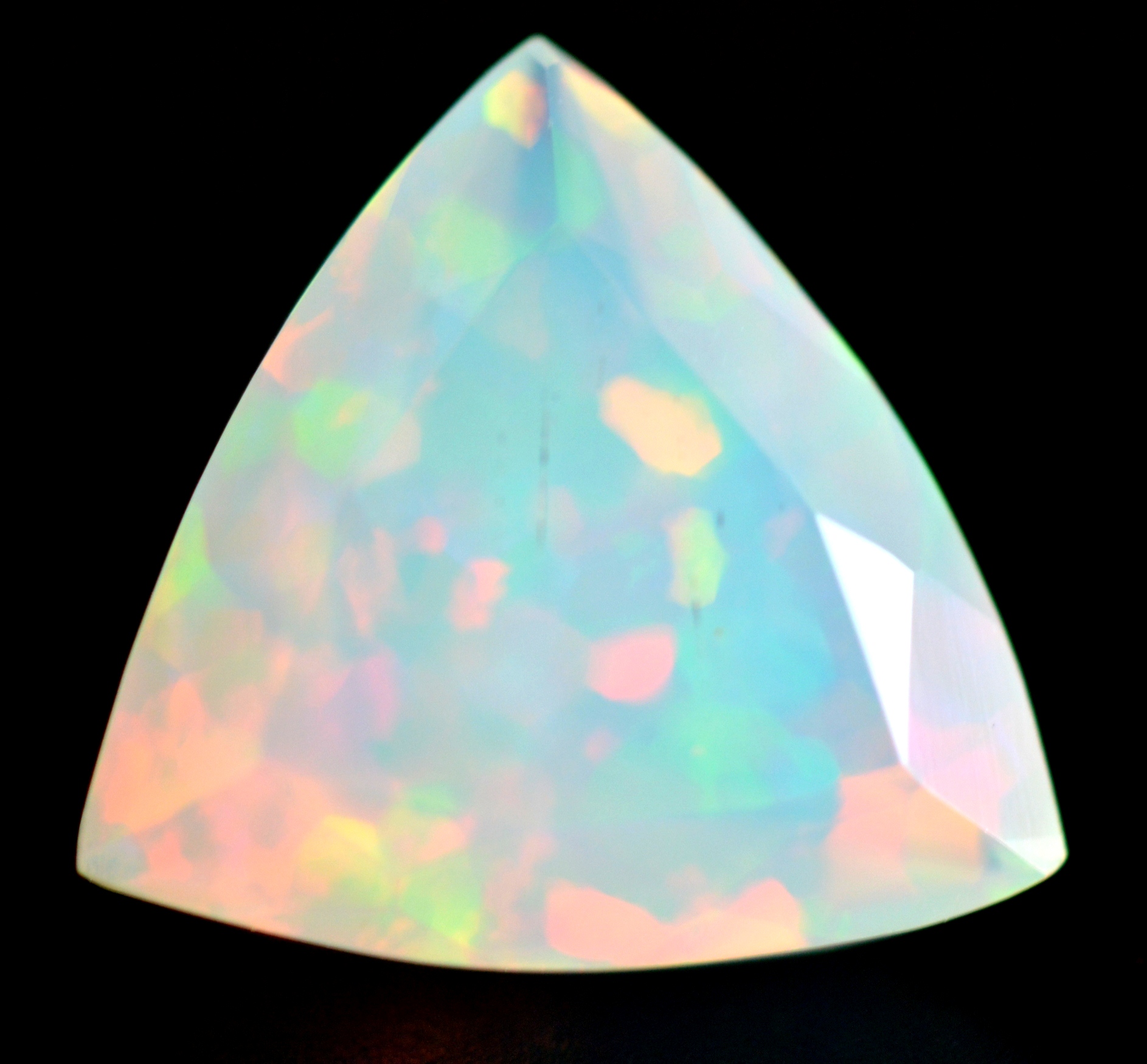

Precious Opal

© Kirk Feral 2009-present, All Rights Reserved. These materials may be duplicated for educational purposes only. No part of this website may be duplicated or distributed for profit, for commercial purposes, or for posting to another website without the expressed written consent of the copyright holder.

It's interesting to note that gemstones which do contain detectable paramagnetic metal ions have a push-pull relationship with the magnet. They are simultaneously diamagnetic, with most of the gem’s chemical composition being weakly repelled away from the magnet, and paramagnetic, with trace impurities of metal ions dispersed throughout the gem being attracted toward the magnet. In most cases, the pull force is strong enough to overcome the repel force. In rare instances, a weak paramagnetic pull will be exactly balanced by the weak diamagnetic repulsion, and the gem will show no response to a magnet in either direction. This is the truest example of an inert response, but we refer to this rare response and the much more common diamagnetic response both as "inert".

About a third of all gem-quality minerals are diamagnetic and show a weak repulsion to a magnet. Not all are colored by light diffraction, color centers or other color-producing processes. Some simply have very low concentrations of metallic chromophores such as iron or chromium. The repel responses of diamagnetic gems help us separate them from gem types that are attracted to a magnet. In this website, we apply the same terminology used to describe the strength of gem fluorescence (inert, weak, moderate, strong) to the strength of a magnetic response. We use the term "inert" to refer to the absence of magnetic attraction, which is characterized by a repel magnetic response (diamagnetic). Throughout this website we use the terms "inert" and "diamagnetic" interchangeably.

Red Fluorite

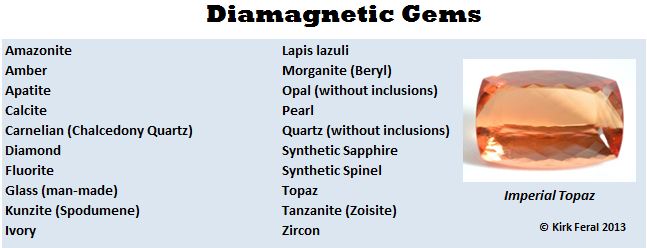

Diamagnetic (Non-magnetic) Gems

Some gems, such as Topaz and Opals with play-of-color, are not colored by paramagnetic metal ions. Their color is due to processes such as light diffraction from tiny spheres of silica (ex. Opal), or defects in the atomic structure of the crystal that give rise to color centers (ex. Topaz). Irradiation is often involved in the production of color centers. Gems colored in these ways are "non-magnetic" or inert (diamagnetic), meaning they show no attraction to a magnet. Instead, they are repelled by a magnet when floated on a raft in water (see video below).

Most solid substances from glass beads to jellybeans are weakly repelled by a magnetic field. These substances don't contain enough unpaired electrons to create magnetic attraction. A repel response indicates Diamagnetism, a type of magnetism in which the induced magnetic field opposes the applied magnetic field of the magnet.

For the purposes of gem identification, we will loosely use the term "primary" gemstone when referring to the gems that are most commonly found in jewelry, such as the species mentioned above. About 200 types of minerals produce gem-quality crystals, and of these, only about 20 to 40 minerals account for all the primary gems fashioned into jewelry. Many gems referred to here as "secondary" gemstones are less common and often rare gemstones. These may be fashioned for collectors, but they are often too soft, fragile or rare to be used in most jewelry, or are not consistently available for jewelry. Fluorite, Apatite, Kyanite and Calcite are examples of secondary gems that are typically diamagnetic. The less common gems often rank low on the hardness scale and are therefore easily scratched. In introductory gem identification classes, instructors are most concerned with the primary gems.

Some diamagnetic gems that can derive all or most of their color from color centers include Diamond, Zircon, Spodumene and Quartz. The varieties of Quartz with color centers are Amethyst, Citrine and Smoky Quartz. All these gems show magnetic repulsion rather than attraction.

Paramagnetic metal ions are often trapped in color centers in gems, but the concentration of these metal ions is too low to be detectable with a magnetic wand. Strong gem color can sometimes be induced by color centers when metal ions are present in only a few parts per million.

Weakly Magnetic "Madeira" Citrine

Kunzite (Spodumene)

Zircon

Blue Kyanite

Yellow Apatite

A rare exception in Quartz are certain Citrines that are colored by iron impurities rather than (or perhaps in addition to) color centers, such as some natural red "Madeira" Citrines from Brazil, and on rare occasions even yellow Citrines. These rare Citrines can be weakly magnetic.

Amethyst (Quartz)

Gems of organic origin such as Pearl, Ivory, Amber, Coral, Shell and Jet are not colored by paramagnetic metals. All organic gems are inert (diamagnetic).

Tahitian Pearl

Dominican Amber

Black Coral

Below is an alphabetical list of 20 of the most common gems that are typically inert (diamagnetic). In a few of these cases, such as Apatite, Calcite and Glass, gems occasionally show magnetic attraction due to metallic coloring agents. In other diamagnetic gems such as Quartz and Common Opal, macroscopic and microscopic inclusions can result in magnetic attraction due to paramagnetic inclusions.

20 Common Diamagnetic Gemstones

This Citrine Shows a Diamagnetic Response

Blue Topaz (Irradiated) and "Imperial" Topaz

Topaz as a gem species is diamagnetic. Regardless of color, Topaz gems don't show magnetic attraction, with the rare exception of Topaz gems that contain large inclusions of a magnetic material such as Garnet. "Imperial" Topaz is colored by chromium in addition to color centers, but the amount of chromium is too small to be magnetically detectable.

Brown "Sherry" Topaz

All diamagnetic responses in gems are extremely weak, and the repel force is fairly constant among different gem types. The extreme sensitivity of our magnetic wand and floatation method makes it possible for us to observe the diamagnetic responses of gems.

Magnetism in Gemstones

An Effective Tool and Method for Gem Identification

© Kirk Feral